Circularity of solar mini-grids in Africa

Solar mini-grids are among the most promising routes to universal energy access in Africa. Integrating circularity, skills training and supportive policies can make them resilient, affordable and sustainable, while creating local jobs for the continent’s growing youth population.

Solar mini-grid developed by Ceesolar and funded by All On in Oweikorogha Community, Bayelsa State, Nigeria on 4 October 2024. Photo: All On.

Almost 600 million people in Africa still lack access to electricity. This contributes to both development and climate challenges, as reliable electricity underpins economic activity and essential services such as education and health. In rural areas, limited electricity not only restricts students’ evening study hours but also prevents health clinics from maintaining reliable cold chains for medicines and vaccines. As a result, many off-grid communities rely on diesel generators or kerosene lamps, which are inefficient, costly and polluting. At the same time, extending national grids into remote or sparsely populated regions is often expensive and technically difficult, making decentralized solutions increasingly important. In this context, solar mini-grids that generate and distribute power locally have emerged as one of the most affordable, practical and scalable pathways for rural electrification.

Over the past decade, international finance and development programmes have accelerated the rollout of off-grid solar technologies, which include both small solar home systems and larger village-scale mini-grids. By the end of 2023, global off-grid solar capacity had reached 4.1 GW, while total off-grid renewable power capacity stood at 11.1 GW. Development finance institutions and blended finance initiatives have helped reduce financial risk for developers and pilot projects have shown how mini-grids can bring electricity to communities beyond the reach of national networks. For example, in Nigeria British International Investment has supported companies in early-stage markets by providing funding and supply chain assistance to lower upfront costs for developers. These interventions unlock private capital and make deployment feasible in areas where commercial investors might otherwise be hesitant.

However, as deployment accelerates, a serious problem is emerging. Many low-cost off-grid devices designed to keep prices affordable have short lifespans. This results in broken batteries, failed inverters and worn solar components accumulating in communities. At the same time, most regions lack robust infrastructure for the safe repair, collection, or recycling of these systems. As a result, solar e-waste is accumulating in many regions and, where informal or unsafe disposal occurs, poses toxic pollution and public-health risks. This challenge is evident across different states in Nigeria, particularly in the informal handling and recycling of used lead-acid batteries. The growing waste stream threatens not only the environmental gains of energy access but also public health and social equity.

Across the region, researchers and programmes are starting to demonstrate the potential of circular solutions. In Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology estimates that with proper collection and recycling systems in place, end-of-life photovoltaic (PV) modules could yield roughly US$4 million in recoverable materials. Parallel initiatives, including programmes under the Sustainable Energy for Smallholder Farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa project, are addressing collection, maintenance and refurbishment within off-grid solar systems. Together, these examples illustrate that circular approaches are technically feasible, while also underscoring the risks if such strategies are not scaled.

Circular solar requires rethinking how energy systems are designed, operated and managed through to end of life. Rather than following a linear process of production, use and disposal, circular solar promotes three interconnected goals:

- Keeping value within the system for as long as possible;

- Reusing systems and components in second-life applications; and

- Recovering materials safely when components reach end-of-life.

For mini-grids, this approach translates into six practical actions:

Mini-grid technologies should be designed for circularity so that materials and components can be easily maintained, reused, and safely recycled at end of life. This requires the use of non-toxic, modular, and standardized components, supported by clear technical documentation. Such design approaches simplify repair processes and strengthen Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) schemes by enabling manufacturers to take responsibility across the product life cycle. Evidence from studies on sustainable e-waste management in developing countries highlights ecological design as a critical enabler of effective EPR systems, contributing to improved collection, recycling, and environmental outcomes.

Modules and other system components should be modular, clearly labelled and designed for disassembly. This allows local technicians to maintain and repair systems easily. Designs that cut costs but prevent repair can trap projects in repeated replacement cycles, increasing both expense and waste.

Accredited repair centres, spare-parts supply chains and technician training improve reliability and reduce operational costs, while also creating skilled employment. Pilot refurbishment initiatives in Ghana and other markets show that basic diagnostics and component repair can significantly extend the useful life of batteries and other system components.

Electric vehicle (EV) batteries and solar PV modules that still have usable capacity can be tested, certified and re-deployed to less demanding applications, such as household backup or community storage. This approach keeps value in the system longer and reduces the need for new materials.

When systems finally reach end-of-life, formal take-back schemes and certified recycling prevent hazardous waste harming the environment and recover valuable materials for reuse.

Leasing or product-as-a-service models let providers retain ownership and benefit from long-term system performance. Digital monitoring systems can track performance and component health, helping operators schedule maintenance and identify batteries or modules suitable for reuse or recycling.

These practices reduce downtime and replacement costs. Second-life batteries lower capital expenditure, while business models that tie returns to system durability encourage proper maintenance. Nevertheless, challenges remain: most solar modules are still optimized for cost and energy output by manufacturers rather than disassembly and repairability. Also, recycling can be uneconomic at small scale, unless policy measures support collection and processing.

The Circular Economy Powered Renewable Energy Centre (CEPREC) is a UKRI-funded, pan-African research programme that unites universities, industry partners, and government bodies to apply circular economy principles to renewable energy systems. Its goal is to support Africa’s energy transition while preventing unmanaged waste and resource loss as off-grid and mini-grid technologies expand. CEPREC currently operates in six countries: Nigeria, South Africa, Kenya, Sierra Leone, Namibia and Rwanda.

The centre focuses on the parts of the mini-grid value chain most prone to component failures, short lifespans and ineffective end-of-life management. Its research explores how second-life EV batteries and power electronics can be repurposed for stationary energy storage, as well as examining business models such as leasing or product-as-a-service to improve long-term affordability and systems performance. CEPREC also maps material flows to help determine where facilities for testing, repair, refurbishment and processing should be located and develops training programmes to certify local technicians in reusing components.

Alongside the technical work, CEPREC engages with policymakers and financial institutions to encourage procurement and investment decisions that account for lifecycle performance in addition to upfront cost. Their integrated approach demonstrates that technology development, skills training, viable business models and supportive policy must advance together to scale circular energy solutions effectively.

Blended finance mechanisms have played a key role in early deployment by reducing risk and improving procurement efficiency. Initiatives such as British International Investment’s Hardest-to-Reach programme and its collaboration with Odyssey on the DARES programme in Nigeria have helped lower pre-revenue barriers for developers. However, scaling circular mini-grids requires more than finance; it depends on technical expertise, strong institutions and coordinated action.

Alongside these financial mechanisms, research partnerships such as CEPREC provide the technical evidence, capacity building, engineering training and operational models needed to make circularity feasible in real-world settings. For meaningful and lasting change, three strands of action must work together:

- Locally grounded research co-produced with African partners;

- Project finance linked to circular and lifecycle performance metrics; and

- Investment in institutional capacity, including accredited repair centres, certified testing labs and effective regulatory oversight.

Rwanda offers a practical example of this integrated approach. The country is advancing national e-waste strategies and exploring policies that embed end-of-life management directly into energy access projects, including solar.

When finance, research and local capacity development align, they reinforce each other. Public finance reduces risk for developers, research informs system design and operational decisions, and strong local infrastructure makes repair, second-life use, and recycling commercially viable. CEPREC’s programme brings these elements together so that circularity becomes a core part of energy access planning rather than an optional add-on.

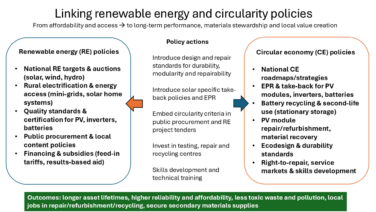

Making circular solar PV mini-grids standard practice will require much stronger alignment between renewable energy policy and circular economy policy. This is especially important for areas such as e-waste management, repair, reuse and materials recovery. At present, these policy domains are often developed in isolation. National energy agencies tend to focus on expanding access and generation capacity, while environment ministries oversee waste management and hazardous materials regulation. The result is a disconnect that creates gaps in responsibility, financing and oversight across the lifecycle of solar technologies.

The following policy actions can help to bridge these gaps and encourage the adoption of circular solar PV mini-grids as standard practice.

Solar products should be designed for easy repair, with modular parts, clear labels for hazardous materials, and accessible repair instructions. Suppliers should provide spare parts for a defined period to reduce failures and make repair viable. In countries without local manufacturing, original equipment manufacturer (OEM) representatives should support design management to ensure compatibility with repair standards.

Importers and manufacturers should help fund the collection and recycling of used solar systems, working alongside informal markets and supporting local repair and refurbishment. An EPR framework for solar products and batteries assigns manufacturers clear end-of-life obligations and secures predictable financing for collection, safe dismantling and high-value material recovery. EPR schemes can also set targets for reuse, repair and recycling, encouraging more durable and modular designs and improving oversight of transboundary movements of used panels and batteries.

Donors, development finance institutions and government procurement agencies should prioritize projects that include repair plans, maintenance agreements and reuse pathways. Preferential financing can encourage providers to take responsibility for full lifecycle management. In the medium term, all new project contracts should explicitly require provisions for repair, maintenance, component recovery and end-of-life recycling to ensure that systems remain functional, safe, and circular throughout their operational lifespan. Embedding these obligations contractually helps prevent premature disposal, reduces waste and aligns public investments with sustainable solar deployment.

Governments and development partners will need to develop local and national facilities for testing, repair and recycling, including screening imported used electrical and electronic equipment. This ensures that it is not classified as electrical and electronic equipment waste, thereby discouraging the import of energy-linked e-waste, but ensuring access to affordable equipment for second-life applications (e.g., EV batteries, inverters). These hubs can reduce costs through scale, create skilled jobs and support the certification of refurbished components. Further, government grants combined with low-interest loans and tax incentives can help early pilots of product-as-a-service models, second-life battery certification and digital tracking platforms reach commercial viability. Over time, these models can become self-sustaining.

Building a circular solar mini-grid industry requires substantial investment in skills and technical capacity, as many of the competencies needed for repair, refurbishment and high-value recovery are currently limited or absent in most local markets. Priority areas include the ability to safely diagnose and grade used lithium-ion batteries for second-life applications, repurposing EV batteries for stationary storage, carrying out advanced fault detection on inverters and charge controllers (devices that regulate battery charging and ensure safe operation), and performing high-quality repair of PV modules and components. Technicians also need training in safe dismantling practices, performance data logging and compliance with emerging e-waste and battery management regulations.

Together, these measures can bring renewable energy and circular economy policies into closer alignment and expand energy access without generating unmanaged waste streams, while generating skilled employment, lowering long-term system costs and safeguarding public health and the environment.

The growth of mini-grids in Africa reflects both major progress and rising systemic risks. Distributed solar systems are transforming communities, yet rapid expansion without attention to repair, reuse and end-of-life practices is generating new environmental and social challenges.

Programmes such as CEPREC show that a more integrated pathway is possible. Mini-grids become far more sustainable and resilient when they are planned, financed and operated with circularity in mind. The decisions made now will determine whether deployment continues in a way that pushes costs and environmental impacts into the future, or whether circular principles are embedded to support a cleaner, fairer and longer-lasting energy transition.

If these recommendations are put into practice, solar mini-grids can remain both a powerful tool for expanding energy access today and a durable and sustainable infrastructure for the decades ahead.